When I speak publicly about African American history in Williamson County, it often surprises the audience to learn that in the 1860 Census more than half the population of the County consisted of enslaved African Americans - more than 12,000 people living here at the time were black. One of the next questions is often - where did they go? Less than ten percent of the population today is made up of African Americans. Well, part of the answer lies in a migration out of the South in the decades immediately following the Civil War.

During the 1870s and early 1880s, thousands of formerly enslaved people left the south for Kansas and other northern and western states in an exodus. This was the first voluntary, mass migration of African Americans in America. The emigrants to Kansas are called "Exodusters" and many of them had their roots in Williamson County. Kansas was attractive to them because of its long tradition of advocating for abolition before the Civil War - such as the events during the Bleeding Kansas era and the fame of abolitionist John Brown.

Exodus to Kansas. The explosion in the African-American population in Kansas was extraordinary. In 1855, only 151 free blacks and 192 enslaved African Americans were counted living in the territory. By the 1870 census, 17,108 black people were living in the state. In 1880, the number of African Americans in Kansas had grown to 43,107.

Some emigrants from middle Tennessee traveled by rail or overland. Most, however, took a steamship up the Cumberland River from Nashville to Paducah, Kentucky where the river joins the Ohio, to Cairo, Illinois and the mighty Mississippi. Their steamship would have followed the Mississippi north, to St. Louis and then traveled west along the Missouri River to the river cities of Kansas City, Missouri, and Wyandotte, and Atchison, Kansas.

Approximate Route taken by many Exodusters traveling by riverboat from Nashville to Kansas.

|

|

| Benjamin "Pap" Singleton Courtesy Kansas Historical Society |

Benjamin "Pap" Singleton. Much of this Exodus was orchestrated by a man named Benjamin “Pap” Singleton. Singleton had been enslaved in Tennessee before the Civil War and managed to escape to freedom in the north. He lived in Detroit and participated as a conductor on the Underground Railroad. By 1869 he had returned to Nashville where he organized the Tennessee Real Estate and Homestead Association - a real estate company that helped organize groups of African Americans to move out of the south, especially the Nashville area. Some of Singleton's original papers can be viewed here.

|

| In 1869, Singleton organized his real estate company. Courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society. |

The emigrants from Tennessee to Kansas in the early 1870s seem to have started a trend that really exploded across the south in 1879. To fully understand what was happening at that time - and how it impacted local Williamson County residents, I have created a timeline below describing significant events related to this important historical time period.

Williamson County Exoduster Timeline

Homestead Act of 1862. This federal law provided 160 free acres of federal land to any citizen who could settle on the land and farm it for five years. Some of this land was in Kansas and was attractive to many southern African Americans looking for a new start in the west during Reconstruction

|

| “Negro Exodusters en route to Kansas, fleeing from the yellow fever,” Photomural from engraving. Harpers Weekly, 1870. Historic American Building Survey Field Records, HABS FN-6, #KS-49-11. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (106) |

1873. First Group of Exodusters Left Nashville. In 1873, Singleton led a group of 300 people to Baxter Springs in Cherokee County, Kansas to form the "Singleton Colony." One early settler in Baxter Springs was Sgt. Abe Boyd, a USCT veteran from Williamson County. Other early Exodusters stopped in Wyandotte, but others continued to Topeka and established "Tennessee Town." Singleton soon organized another colony to come from Lexington, Kentucky and settle in Graham County - this would be the settlement of Nicodemus.

1874. Dunlap Colony. In early 1874, another group of Tennessee Exodusters established the Dunlap colony, near the present town of Emporia, Kansas.

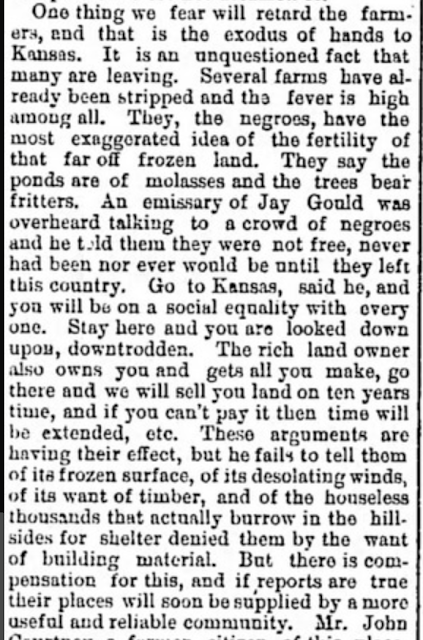

April 1875 - Williamson County Exodusters. In April 1875, a Nashville newspaper reported on the growing movement that "It is an unquestioned fact that many are leaving. Several farms have been stripped [of their farm hands]." Evidently, 500 local families from Williamson County with "Kansas fever" hired a steamboat captain to take 2,000 people to St. Louis on their way to Kansas. A Kansas newspaper opined that "What Tennessee loses, Kansas gains, for we have no doubt that those composing this party are steady and industrious; and though bringing no wealth to our State will be a valuable addition to our population."

Henry Crump Family. Among those Exodusters was Henry Crump and his wife Louisa "Lulu" Kinnard from Williamson County. According to an article in "The [Franklin] Review and Journal" (April 20, 1875) "About sixty negroes left the neighborhood of College Grove last week for Kansas. Like the Arab, they folded their tents and gently left. . . . "

|

| Jackson TN Whig_and_Tribune_Sat__Apr_17__1875 |

|

| The_Topeka_Weekly_Times Thu__Apr_15__1875_ |

|

| The_Leavenworth (Kansas) Times_Sun__Apr_11__1875 |

|

| The_Nashville Republican Banner_Thu__Apr_29__1875_ |

April 30, 1875 Lynching of Joe Reed. On April 30, 1875, a man named Joe Reed (originally from Franklin, Tennessee) was lynched and hung from a bridge over the Cumberland River in Nashville. Reports are somewhat unclear as to whether he survived the attack when he fell into the River. Some believed he made his escape to Kansas. Nevertheless, the incident inflamed passions and the event was not easily forgotten by the African American community.

May 1875 Emigration Meeting in Nashville. The following month, interest was growing in a mass migration to Kansas. A meeting was held in Nashville to elect delegates to a State Emigration Convention to discuss a mass exodus. The attendees pointed to several factors for pursuing emigration including the Reed lynching, the inability to get fair pay for their work, and the failure of officials to enforce their rights. A newspaper reporter stated this:

Not to particularize - the speeches delivered were about in this strain: That it was the interest of the colored people of Tennessee, and especially of this locality, to emigrate; because they could not get work to do, or just compensation for what work they performed; because neither the laws nor their enforcement were adequate to the protection of the negroes in their rights; because there was little or no hope for the prosperity and happiness of the colored people in this State. The recent lynching of Reed was cited with indignation and denounced by some of the speakers. The deed of murder perpetrated by Reed met with the strongest disapprobation, but the official neglect, which permitted him to be mobbed, was an outrage on the colored people and demanded the severest condemnation. Such was the character of the complaints raised. The best remedy, it was generally agreed, was to be found in emigration. No one proposed a better country, but it was declared the interest of the colored people to get out of this. Calmness and deliberation were advised in the prosecution of the measure before the colored people. The object of the State Constitution was alluded to as being to devise some systematic plan of exodus.

A week later, the full state Convention on Emigration convened. Thomas Crump of Franklin represented Williamson County. His uncle Henry Crump had been one of the early Exodusters the previous April. Following this meeting, a five-person Bureau of Emigration was established to research the states of Kansas, Mississippi, and Florida, and "about September the colored people of Tennessee could determine whether to emigrate or not. . . . The resolutions evinced a tone of enmity against the Grangers [white landowners], who, according to the language contained in them, had gained such control over the State, that the negroes were unable to obtain a living price for their labor."

A week later, the full state Convention on Emigration convened. Thomas Crump of Franklin represented Williamson County. His uncle Henry Crump had been one of the early Exodusters the previous April. Following this meeting, a five-person Bureau of Emigration was established to research the states of Kansas, Mississippi, and Florida, and "about September the colored people of Tennessee could determine whether to emigrate or not. . . . The resolutions evinced a tone of enmity against the Grangers [white landowners], who, according to the language contained in them, had gained such control over the State, that the negroes were unable to obtain a living price for their labor."By the end of the month, the Board of the Convention had met again and appointed one agent per each middle Tennessee county "whose heart is in the work." Once again, Franklin's Thomas Crump was appointed to the task. I have written about Thomas' family before - if you are interested in learning more about him and his amazing family you can find the post here. Thomas never did become an Exoduster in the true sense, but he did eventually leave Tennessee and move to Chicago, Illinois.

August 15, 1875 Report from Kansas. In August 1875, Henry A. Napier (older brother of well-known Nashvillian J. C. Napier) returned from a trip to Kansas to scout locations for emigration and gave a report on his findings to the State Emigration Convention at Lindsley Grove in the Edgefield area of Nashville. He said one or two families from Tennessee had already settled in Great Bend, Kansas 280 miles from Topeka. Napier described the soil, timber, fuel sources, crops and pests, and climate. He also gave a detailed list of what any planning emigres would need to have available to successfully make the move and said they would need about $1,000. He said, "Many who left Tennessee last winter with the intention to go to South Kansas, stopped in St. Louis for want of means, intending to get labor and proceed to Kansas, but there was no labor that they could get, and from cold and other exposure they took the small pox and died. Others went as far as Kansas City with the same intention, and there in a more deplorable condition than they were at home they became objects of public charity.. . . "

|

| Nashville_Union_and_American_Fri__Aug_27__1875_ |

These rather dire reports do not seem to have slowed the tide of Exodusters from Williamson County. By that fall another group of 75 people were reported to have left for Kansas City, "forced to leave . . by the grangers, who refused to pay them more than fifty cents a day for their labor."

|

| The_Workingman's_Courier (Independence Kansas) Thu__Nov_25__1875 |

|

| Nashville Daily American Wed__Nov_29__1876 |

|

| Emmanuel Lawrence Born in Green County, Georgia Enslaved in Tennessee |

|

| Mary Jo Lawrence Married in Williamson County Emigrated with her husband Emmanuel to Topeka in 1876 |

|

| The_Nashville Daily American Thu__Mar_16__1876_ |

|

| The T. T. Hillman steamer circa 1878 The Louisville (KY) Courier Journal, Sat Oct 1,1938 |

. . . Octoroons and dusky maidens whispered words of encouragement to their sweethearts, tall, strapping fellows, with countenances as dark as night, and who referred to a future of unalloyed joy awaiting them in the land of the colored man's longing. Sons and daughters bade farewell to parents, whose declining age could not induce them to pause and reconsider their action. Old men and women, whose forms were bent with the weight of years, bade a tearful adieu - perhaps an eternal farewell - to those whom they once kept time to the music of the fiddle and the pickings of the banjo on the plantations in days gone by. Even the little children, well-aware, even in their simplicity, that their playmates were going to leave them, seemed sad at the thought of parting with each other. Numbers of antiquated muskets and timeworn axes were jauntily born by the heads of families and young men. Trunks, boxes, bundles of every size and description, churns, and a vast amount of miscellaneous household articles, were unloaded from wagons and carried on board by dozens of willing hands. Having taken deck passage, the emigrants were stored away in every conceivable place. . . . The fares of eighty-three persons were paid, and Captain Ambrose was directed to land them all at the Hillman Iron Works, where those who had not paid could do so and be taken back on board. In order to induce stragglers to hurry up, the whistle was sounded several times, and in a few minutes the avenues leading to the wharf were converted into trotting courses, numbers of women running toward the boat at full speed, vigorously waving their sun-bonnets and handkerchiefs at the officers as a signal to wait for them. At 5 o'clock the plans were drawn in, the bell rang; the wheels commenced revolving, several excited negro men made very brief and incoherent speeches, the steamer glided out into the tide, and cheer after cheer burst from the throats of over five hundred on the wharf. As the Hillman glided down the river, hundreds of handkerchiefs, hats and bonnets were waved as a parting salute, and the boat was soon lost to view. . . . Twenty-five negroes left here by rail Tuesday night and twenty-five yesterday. The Louisville and Southeastern depots were crowded with colored folks yesterday morning, some of them actively discussing Kansas and the means of getting there, while those who had money were purchasing tickets for the West. It is safe to say that there were at least one hundred and fifty on hand to see the twenty-five depart, and that one hundred of these would have gone had they been able to pay their fare. . . .Gone to meet Joe Reed! [a reference to a man who was the possible escaped lynching victim]"

|

| This photograph depicts a steamboat [perhaps the T. T. Hillman?] containing Exodusters in Nashville, Tennessee, with Benjamin "Pap" Singleton and S. A. McClure superimposed in the foreground. Dated 1876. Courtesy Kansas Historical Society. |

Summer of 1877 In the summer of 1877 the Nashville African American community held a series of meetings regarding the exodus. These meetings were chiefly organized by Benjamin Singleton and his company to recruit emigrants.

|

| Courtesy Kansas Historical Society. |

|

| Courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society |

|

| Courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society |

That same year, two songs were written in Nashville regarding emigration. The lyrics help explain the emotion and thinking behind the desire to emigrate:

The Land That Gives Birth to Freedom

"We have held a meeting to ourselves to see if we can't plan some way to live,

Chorus - Marching along, yes we are marching along, to Kansas City we are bound,

We have Mr. Singleton for our Provident, he will go on before us and lead us through,

Surely this must be the Lord that has gone before him and opened the way,

For Tennessee is a hard slavery state and we find no friends in that country,

Truly it is hard, but we all have to part, and flee into a strange land unknown,

We want peaceful homes and quiet firesides, no one to disturb us or turn us out."

Extending Our Voices to Heaven

Farewell, dear friends, farewell,

We are on our rapid march to Kansas, the land that gives birth to freedom,

May God almighty bless you all, Farewell, dear friends, farewell,

Many dear mothers who are sleeping in the tomb of clay

Have spent all their days in slavery in old Tennessee,

Farewell, dear friends, farewell,

The time has come we all must part, and take the parting hand,

Farewell, dear friends, farewell,

It seems to me like the year of Jubilee has come, surely

this is the time that is spoken of in history

Farewell, dear friends, farewell,

|

| Courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society |

Williamson County's 1877 Exodusters. About 1877 Joanna Crutcher and her husband Felix “Grundy” Thompson left Williamson County and moved to Topeka, Kansas. Grundy's brother David was a Buffalo Soldier and had been stationed out west already with the 9th Cavalry. David eventually joined Grundy in Topeka. The brothers left behind their older sister Julia Thompson Johnson who remained in Franklin to raise her family - including two sons who served in Europe during World War I.

On March 18, 1878, Benjamin Singleton announced that he would lead a group from Nashville to Kansas on April 15, 1878.

|

| Courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society |

|

| Portions of Handbills for Singleton's real estate company. Courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society. |

Great Exodus in 1879 By 1879, the trickle of small groups of emigrants leaving Tennessee - and other southern states - for Kansas had turned into a flood.

|

Memphis_Daily_Appeal

Mar_20__1879

|

March 1879. The Memphis newspapers were reporting - in a derogatory way - in the spring of 1879 that "about two hundred negroes, from the counties of Williamson, Marshall and Rutherford, arrived in the city yesterday morning and left last night for the land of milk and honey - Topeka, Kansas. Half of them went via Louisville and half by another route. They represented all colors, between the octoroon and the full-blood; all ages, from one month to sixty years. Their baggage was done up in dry goods boxes, trunks, valises, carpets and newspapers. The entire company were accompanied by a 'yaller dog.' These negroes are, doubtless, attracted toward Kansas by representations similar to those made to the unfortunate colored people who have recently created such a senstation in St. Louis . . "

Among this group may have been Abbey Terrill Williams, Isham Fitzgerald, Allen Beach, and Green Currin with his wife Caroline Starnes - all of whom were Williamson Countians who I have identified as moving to Kansas during this period just before 1880.

The following month, according to reports, 1,000 people from Nashville arrived in Wyandotte, Kansas (perhaps some were from the group leaving Williamson County in March) and camped at the mouth of the Kaw River. Some crossed the Kaw River into North Topeka and set up a community known as Redmonville; I believe it may have been named Redmonville for several families of Redmons from Williamson County who settled there.

Sometime between 1870 and 1880, a woman named Harriet Redmon emigrated to Topeka with her three adult sons John, George, Joseph and several other children. All three men brought wives and families with them as well. Joseph and George had married their wives in Williamson County. These families settled in what was named the Redmonville area where they were successful members of the community.

Among this group may have been Abbey Terrill Williams, Isham Fitzgerald, Allen Beach, and Green Currin with his wife Caroline Starnes - all of whom were Williamson Countians who I have identified as moving to Kansas during this period just before 1880.

|

| "The Negro exodus - Scenes on the wharves at Vicksburg" James Henry Moser, 1879 Illustration in: Harper's weekly, (1879 May 17), p. 384 Courtesy of the Library of Congress |

The following month, according to reports, 1,000 people from Nashville arrived in Wyandotte, Kansas (perhaps some were from the group leaving Williamson County in March) and camped at the mouth of the Kaw River. Some crossed the Kaw River into North Topeka and set up a community known as Redmonville; I believe it may have been named Redmonville for several families of Redmons from Williamson County who settled there.

Sometime between 1870 and 1880, a woman named Harriet Redmon emigrated to Topeka with her three adult sons John, George, Joseph and several other children. All three men brought wives and families with them as well. Joseph and George had married their wives in Williamson County. These families settled in what was named the Redmonville area where they were successful members of the community.

|

| Photograph of Kansas Exodusters |

As the waves of Exodusters began to arrive, many with poor clothing, little money, and few resources, a humanitarian crisis began to develop.

|

| ANC Williams of Franklin, Tenn. |

May 6-9, 1879 National Conference of Colored Men of the United States was held in Nashville. Two delegates from Williamson County attended - ANC Williams from Franklin and D. W. Williams from Brentwood. This meeting was a nationwide meeting that met in Nashville to discuss issues of relevance to African Americans during this turbulent time. One issue of importance was the exodus and the forces that were leading to it. According to the published proceedings, a Committee on Emigration was convened to study several

questions related to the mass migration. Their report concluded, in part, regarding "the causes that have given rise to the migration among the colored people of the South", that "some of the most potent causes: were (1) this migration movement is based on a determined and irrespressible desire, on the part of the colored people of the South, to go anywhere where they can escape the cruel treatment and continued threats of the dominant race in the South."; . . (2) "Another important cause is the almost, if not total, failure on the part of any Democratic State administration in the South to faithfully carry out and perform their promises made to the colored people when said Democracy assumed control fo their respective State governments." The Committee appointed a smaller group to further investigate - and to call on Congress to investigate - the status of emigrants who had already left for Kansas and the west and to report back in the fall.

|

| Governor John P. St. John |

- In early August of 1879 Thomas Crump held a meeting at the courthouse in downtown Franklin to discuss the exodus. According to newspaper reports, Crump favored "staying at home and [fighting for civil] rights - such as serving on juries and not being compelled to ride in [train] box cars." Despite Crump's position, the reporter said that it seemed there would be a "considerable tide of emigration to Kansas in the fall." The report stated that an "old colored man rose and said he wanted to know the how and the when."

Senate Hearings into Exodus. In the Fall of 1879, Congress responded to the calls for action by African American leaders and appointed a Select Committee of the Senate on December 15, 1879, charged with finding out why so many people were emigrating north. The committee interviewed 153 African Americans between January 19, 1880 and February 23, 1880. Nashville's "Moses" - Benjamin Singleton - was among those interviewed. In his testimony, Singleton stated that he had already helped to bring 7,432 people from Tennessee to Kansas. You can read the full Senate Report here.

Many of these Redmons married other Williamson Countians who were also Exodusters. For example, George Redmon's daughter Martha married Jack Austin, the son of Jim and Regina Austin - who had moved to Topeka around this time. Another Redmon daughter Maria married James Street, another Williamson County Exoduster. Their son was Reuben Street who I have written about previously.

In 1882, US Colored Troop veteran Granville Scales moved to Topeka, Kansas with his family.

From 1860 to 1880, the African American population of Williamson County dropped from 52% to 44% of the total population. I think we have just begun to fully understand how many families left their homes and loved ones in Williamson County, how they stayed connected once they left for Kansas, and what the impact was on those left behind. Williamson County's Exodusters may not have remained here, but the legacy of their story lives on.

Additional Resources

- Links to several good resources and original documents on the Western Migration

- Good overview of Wynadotte and the political tensions and views of how to help the refugees

- Library of Congress resources on the Western Migration

- video of a lecture by the National Archives regarding the 1880 Senate Investigation

- More information from the National Archives website

- Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction, by Neil Irvin Painter.

|

| Report and Testimony of the Select Committee of the United States Senate to Investigate the Causes of the Removal of the Negroes from the Southern States to the Northern States, Part III 1880 April 17 Tennessee State Library and Archives |

Williamson Countians Settling in Topeka. By the 1880 Census the number of African Americans residing in the area of Topeka, Kansas was 3,648, out of a total population of 15,528. Many of these new residents were Tennesseans who settled in part of the Third Ward that became known as Tennessee Town.

|

African American children, Topeka, Kansas This sepia colored photograph shows a group of African American children gathered in front of a home in the Tennessee Town neighborhood in Topeka, Kansas. The neighborhood was located southwest of the Capitol building. Some"Exodusters" settled in this area of Topeka. Creator: Gates, W.A. Date: June 20, 1900 Courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society |

In addition, as I mentioned before, I believe that the Redmonville area in North Topeka had been settled largely by the African American Redmon family from Williamson County. By 1880 the Topeka City directories include many references to these Redmons living adjacent to each other on Tyler street in North Topeka.

|

| 1880 Radge's Topeka City Directory The Redmon family from Williamson County |

|

| 1885 Topeka City Directory The Redmon family from Williamson County, Tennessee |

|

| 1888 Topeka City Directory The Redmon family from Williamson County |

In 1882, US Colored Troop veteran Granville Scales moved to Topeka, Kansas with his family.

From 1860 to 1880, the African American population of Williamson County dropped from 52% to 44% of the total population. I think we have just begun to fully understand how many families left their homes and loved ones in Williamson County, how they stayed connected once they left for Kansas, and what the impact was on those left behind. Williamson County's Exodusters may not have remained here, but the legacy of their story lives on.

Additional Resources

- Links to several good resources and original documents on the Western Migration

- Good overview of Wynadotte and the political tensions and views of how to help the refugees

- Library of Congress resources on the Western Migration

- video of a lecture by the National Archives regarding the 1880 Senate Investigation

- More information from the National Archives website

- Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction, by Neil Irvin Painter.