Narcissa Brown Reece was born into slavery in Williamson County, Tennessee around 1863. By the 1930s, she was living at 710 Overton Street in Nashville when she was interviewed by a WPA worker named Della Yoe. The published interview appears on pp 64-65 of Volume 16 of the Federal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project. Yoe was an accomplished reporter who served as the foreman of District 1 of the Federal Writer's Project headquartered in Knoxville, TN. She was a white, single woman who - coincidentally - had a sister who had married into the Patton family of Williamson County.

Narcissa Brown Reece's interview is one of six WPA Interviews that I have identified of people with Williamson County connections. You can learn more about these interviews and others here.

Daughter of Mary "Polly" Bradley-Perkins and Randall Brown

Enslaved by the Perkins and Bradley Families of Forest Home

Narcissa Brown Reece was the daughter of Randall Brown and Mary "Polly" Bradley-Perkins Brown. I believe that the couple was initially enslaved by the wealthy Perkins and Brown families, who lived on a series of large farms in the Old Town area on Del Rio Pike and the Old Natchez Trace west of Franklin.

|

| This portion of an 1878 map of Williamson County shows downtown Franklin at the far bottom right, and circled are the landholdings of the Brown and Perkins families along Del Rio Pike and Old Natchez Trace. D. G. Beers & Co. Map of Williamson County 1878 |

Nicholas "Bigbee" Perkins and his wife Mary Hardin Perkins owned large parcels of property and enslaved more than three hundred people in Franklin. They were among some of the earliest white settlers in Williamson County. The couple married here in 1808. In the mid-1820s, it is believed that Polly and Randall were born into bondage in this area.

The Perkins had several children, including two daughters who married into the Bradley family. Mary Elizabeth Perkins married Leland Bradley in 1836, and her sister Margaret Perkins married Robert H. Bradley in 1844. Polly alternatively used the last name Bradley and Perkins during her life. I believe the use of both last names came through these connections among the white enslavers.

[Note: I have researched other people with ties to this white family. Nicholas Bigbee Perkins' son William O. Neil Perkins sold Nancy Perkins Gardner who was interviewed in Oklahoma City by the WPA. She also had relatives with the surname Bradley. Her uncle Judge George Napier Perkins was a US Colored Troop soldier, attorney and activist who was also enslaved by this family.]

During their time in slavery, Narcissa's parents Randall and Polly witnessed the Leonid Meteor Shower. Between November 10th & 12th in 1833, for three consecutive nights, people across North America witnessed the dramatic Leonid Meteor shower. This event was often referred to as "The Night the Stars Fell." Randall and Polly would have been around eight years old. Later, their daughter Narcissa recalled how,

"Mammy told us how the stars fell and how scared everybody got."

When Nicholas "Bigbee" Perkins' father Thomas died in 1838, some of the people he enslaved were hired out to earn money for his family and estate. Among them was, "Girl Little Polly" who was hired to James H. Wilkins. There is no way to confirm whether this Polly was Narcissa's mother, but she may have been. Polly was about 13 years old at the time.

Ten years later, in 1848, Nicholas Bigbee Perkins died. I believe that, as part of the dispersal of his estate, on January 30, 1849, Nicholas Bigbee Perkins' son William O'Neil Perkins sold five enslaved people to Enoch Brown. Among them was, Randal age 22 - Narcissa's father - and Polly, aged 24 - Narcissa's mother. Williamson County Deed Book T, p. 225

Enslaved by the Enoch Brown Family

Narcissa Brown Reece described in her interview how,

"I was born in slavery, in Williamson County ... I think I was four when the war started."

"My mammy and daddy was Mary and Enoch Brown." "My missis and master was Polly and Randall Brown."

After extensive research, I firmly believe that the above statements are a transposition by the interviewer. The names should be the reverse. Narcissa was enslaved by Mary and Enoch Brown. And Narcissa's parents were Randall and his wife Mary "Polly" Brown.

|

| Enoch Brown 1807-1889 |

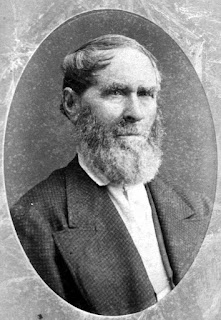

Enoch Brown was born in Brentsville, Prince William County, Virginia in 1807, the middle child of Joseph and Catherine Brown. According to family lore, Joseph Brown was "cruel and unreasonable." Following the death of his wife Catherine in the early 1820s, 13-year-old Enoch, his brothers Thomas and Alexander "Sandy" and sisters Emily and Nancy left Virginia for Tennessee, taking with them an enslaved woman and man.

By 1832, Enoch Brown was living in Williamson County where he married Fannie Cloyd and started his own family. They settled about six miles northwest of downtown Franklin in the Old Town area near the Temple Hills of Williamson County on the Old Natchez Trace - not far from the Perkins landholdings on Del Rio Pike.

|

| A portion of 1878 Map of Williamson County, Tennessee Highlighted portion shows Enoch Brown's 650 acres Hill Home in District 6 west of Franklin |

By 1850, Enoch Brown was widowed and supported his own family by farming using - at least in part - enslaved labor. Living in the household was a free Black man named George Lewis.

|

| 1850 US Census, Williamson County, Tennessee, District 6 A portion of page 6 shows the Enoch Brown household of free people |

Also living on the property were 23 enslaved people, including a 24-year-old male and 22-year-old female who may have been Randall and Polly.

In 1857, Enoch Brown married Mary Innis. Years later, when Narcissa Brown Reece recalled that she was enslaved by "Mary and Enoch Brown" - this was the couple she was referring to. She would have been a toddler at the time of the marriage. By 1860, Enoch Brown was enslaving 31 people on his farm; the oldest was a 48-year-old woman and the youngest was a 1-month-old baby girl. Nine of the 31 people were females. A six-year-old boy was noted as "deaf."

|

| Slave Census, 1860 Williamson County, Tennessee - District, page 35 Entry for Enoch Brown |

Taking into account the difficulty in identifying individuals on these slave schedules with any certainty, it is interesting to note that at the time of the Census, Randall and Polly would have been about 35 years old, and a man and women of about that age appear on the list. Additionally, they would have had five, perhaps six, children by then that I can tentatively match to the ages of enslaved children on this list - including their son Claiborn who would have been six and was indeed deaf. A four-year-old girl could be Narcissa.

Post War and Reconstruction

It is not clear what life was like for Randall, Polly, and their children - including Narcissa - during the Civil War. Randall does not appear to have joined the US Colored Troops, and his name does not appear on the list of men who worked as laborers for the US government during the War. The family may have remained on the Brown farm during the War. In her interview, Narcissa recalled that during this time,

"When freedom was declared we were turned loose with nothing.

My daddy took us down in the country, raised crops, and made us work in the field."

By 1868, the KKK was active in Williamson County and Narcissa described how she:

"Didn't see any Klu Klux Klan, but I always got scared and hid

when we'd hear they were coming.

You can learn more about this time in Williamson County by reading this post.

In 1870 the family was counted by name for the first time in a census. Narcissa was counted as being seven years old - the seventh of Randall and Polly's ten children living at home. This indicated she was born around 1863. Two of her siblings, older brother Claiborn and next younger sister Mary, had both been born deaf and were mute. The family was living in District 6 of Williamson County, near the Enoch Brown farm. Narcissa's two oldest sisters at home - Laura and Molly Ann- were both married mothers working as farm laborers. Molly was married to Stephen Davis (aka Stephen Mays), a veteran of the 12th US Colored Infantry during the Civil War. The couple had three young girls.

Narcissa's oldest sister, Matilda was married to Jack Hill and they were also living in District 6, along with Jack Hill's mother and their three young children.

In 1874, the next oldest sister Malvina married Thomas Southall. Tom was the son of Fannie McGavock and Oscar Southall, a painter and farmer. Fannie had been bequeathed to Mary Southall by her mother Sarah McGavock of Carnton. The couple rented land from Fountain Branch Carter (of the Carter House) before they purchased their own property.

In 1876, Narcissa married Daniel Reece in Williamson County.

.jpg) |

| Marriage License of Narcissa Brown and Dan Reese. Note both names are denoted "col" - for "colored." |

Over the next four years, three children were born to the couple: Mary, Floyd, and Pearl. In the 1880 Federal Census, the family was counted living in District 5 next to Narcissa's parents Randall and Polly, and her younger siblings.

Meanwhile, Narcissa's older sister, Laura, was living with Mary Brown, the widow of Enoch Brown, and working as her servant. They appear to have been on the original Brown farm in the Old Town area west of Franklin, Tennessee.

The 1890 Federal Census is missing, but we have a small clue as to some activities that surely caught Narcissa's attention during that time. That fall, her younger brother Manuel Brown, was accused of shooting another man and wounding him. The sons of their former enslaver, Coley and Enoch Brown Jr, hired an attorney to defend Manuel.

|

| The_Tennessean_Sat__Sep_20__1890 |

It is not clear what the outcome of the case was, but Manuel worked as a stonemason and minister in Nashville, where he died in 1936. He was buried in the Greenwood (Mt. Ararat) cemetery.

Narcissa's mother Polly appears to have passed away around this time, and in 1896 her father married a woman named Laura.

1900s - 1920s

Sometime before the 1900 census, Narcissa and Daniel moved to the Southall area of Franklin. The couple were in their mid-to-late 40s and were raising five children and grandchildren.

|

| 1900 Federal Census Williamson County, Tennessee, District 5/113, page 8 |

Their oldest daughter Mary had married a few years earlier and was living nearby on Boyd Mill Pike with her husband Thomas Rivers and their three young children, including infant Narcissa named after her grandmother.

In 1906, Narcissa's father Randall divorced her step-mother Laura citing abandonment. Soon after, Narcissa and Daniel moved their family to Franklin Road on the north side of town in District 8 of Williamson County. In 1910, Narcissa was working as a laundress, and Daniel continued to farm. In her interview, she described how,

"I've cooked a little for other people, but most of my work has been laundry."

In the spring of 1910, Halley's Comet made its appearance in the sky. Narcissa recalled how while she was living in Williamson County,

I saw the long tail comet.

1920s - 1940s

As is the case for so many Black families, the 1920 Census-taker appears to have skipped Daniel and Narcissa Brown Reece. It is not clear exactly what happened during the two decades between 1910 and 1930, but we know that several of Narcissa's sons and grandsons registered for the draft of men to serve as soldiers in World War I. (Learn more about the local African American experience during World War I here.)

|

| In 1918, Naisy and Daniel's son Floyd registered for the draft during World War I. |

|

| Additionally, their grandson Leonard Rivers likewise registered. He was living in the Bingham community west of Franklin on Boyd Mill Pike. He died the same year from pneumonia. |

|

| 1931 Nashville City Directory Narcissa was widowed, living at her home at 710 Overton St in Nashville Living with her were her daughters Mattie and Katherine. |

Their Overton Street neighborhood appears to have been a thriving Black community. A few steps away was a grocery store and beauty school. Today the area is known as the fashionable residential, retail, and restaurant location called The Gulch - complete with baristas, cycle classes, and a Patagonia store.

|

| The Nashville Globe Friday, August 24, 1917, page 8 |

|

| The Nashville Globe, Friday September 6, 1907, page 3 |

On April 1,1936, Narcissa's daughter Mollie died at their home of pneumonia. She was about 42 years old. Her mother was the informant on her death certificate.

WPA Interview.

Around 1937, Narcissa Reece was interviewed by the Works Project Administration at her home on Overton Street. Narcissa was about 79 years old at the time. Some of what she said that day is transcribed below:

I don't know what to say about the younger generation; there is such a difference now to what it was when I was a girl.

I belong to the Baptist Church. I never went to many camp-meetings, but went to a lot of baptizing.

Signs: "Good luck to get up 'before day-light if you're going someplace or start some work. Bad luck to sweep the floor after dark and sweep the dirt out.

Songs: "I Couldn't Hear Anybody Pray." "Ole Time Religion." "Cross The River Jordan."

Songs: "I Couldn't Hear Anybody Pray." "Ole Time Religion." "Cross The River Jordan."

1940s

I have not been able to find Narcissa Reece in the 1940 Federal Census, but I have determined that after her interview, Narcissa moved a few blocks away to a new home at 728 12th Street South. She lived there with her daughter Katherine.

World War II.

Soon after, the US joined World War II. Narcissa Reece's grandson Gentry B. Hardison joined the Army and served as a corporal in World War II and later in Korea. Upon his death in 1959, his remains were buried in the Nashville National Cemetery.

As men went to War in the 1940s, the country experienced a labor shortage that created an opportunity for women. Narcissa's 25-year-old granddaughter Juanita Rivers moved to Pontiac, Michigan where she worked as a core dipper on the automotive line. These women are referred to as "Black Rosies". Juanita Rivers worked for Pontiac Motors for 33 years until she retired in 1975.

|

In 1943, Narcissa's daughter Katherine died in Nashville. She was buried in Greenwood Cemetery like her brother Manuel. At the time, the two women were living together at 728 12th Avenue South.

Death of Narcissa Brown Reece.

On December 23, 1947, Narcissa Brown Reece died at her home at 728 12th Avenue South in Nashville. She was almost 90 years old. Her daughter Polly Reece Hardison was the informant on her death certificate. Her funeral was held at the St. Eli Primitive Baptist Church on Bradford Avenue, not far from her home.

Narcissa Brown Reece's WPA Interview was one of the shortest that I have researched - but her life was one of great consequence. Narcissa began her life as a child in bondage in Williamson County, Tennessee. She lived through the Civil War, the Spanish American War, World War I, and World War II.

|

| The Tennessean December 25, 1947 page 4 |

At the time of her death in 1947, she had eight great-grandchildren, including Charlotte - the daughter of Juanita Rivers Miller. Charlotte and her siblings Pearl and David have been researching Narcissa's story and continue to share and cherish her legacy. You can view a Power Point Presentation that they have generously shared with this blog here. I am very grateful for their assistance with this research.

Federal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 15, Tennessee, Batson-Young. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mesn150/. (Accessed September 28, 2016.)