As soon as the Civil War ended in 1866 Granville and Catherine set about to provide for the future of their children. In the 1870 Census – the first Census which counted all people by name, regardless of race – the couple reported a personal estate worth $1,000 (a large sum in those days) and the three oldest children - all boys - were attending school. Granville also reported to the census-taker that he could read and write. Clearly, education was already a top priority for this family.

Just three years later, during the 1873-1874 academic year, Granville and Catherine’s two oldest sons Thomas (now 18 years old) and John (now 16 years old) were attending Fisk University in Nashville as boarding students for the “Normal Course” – a college preparatory program that included instruction that would help them become teachers such as “Observation and Practice Teaching in the Primary School.” It’s important to remember that this was only seven years after the end of the Civil War and the emancipation of slaves in Tennessee. To be able to send their sons to a University as boarding students in such a short period was a remarkable accomplishment for Granville and Katherine Crump.

During the years of their attendance, the Crump sons would have participated in “exercises in writing, spelling drawing, vocal music, gymnastics, declamation [public speaking] and composition.” The Crump sons would have studied using textbooks such as Ray’s Arithmetic 3rd Part, Guyot’s Intermediate Geography (North and South American and the United States) and Hilliard’s Fifth Reader. In the early days of Fisk, the school operated out of former military barracks and buildings.

Thomas Crump became involved in politics during his time attending Fisk. He was appointed to be the delegate from Williamson County to a convention of African American men discussing the interest in large-scale migration of former slaves to Kansas and other states, called the Exoduster movement.

The brothers also would have heard about the creation of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a choir of students who were on a world-tour raising money to construct a new facility for the school which would later be called Jubilee Hall. In two years, they raised over $150,000 and the building was completed in 1876.

Thomas Crump - who was a gifted singer himself - married the youngest member of the Fisk Jubilee singers, Mary Eliza Walker (at the far right in the photograph).

Just three years later, during the 1873-1874 academic year, Granville and Catherine’s two oldest sons Thomas (now 18 years old) and John (now 16 years old) were attending Fisk University in Nashville as boarding students for the “Normal Course” – a college preparatory program that included instruction that would help them become teachers such as “Observation and Practice Teaching in the Primary School.” It’s important to remember that this was only seven years after the end of the Civil War and the emancipation of slaves in Tennessee. To be able to send their sons to a University as boarding students in such a short period was a remarkable accomplishment for Granville and Katherine Crump.

During the years of their attendance, the Crump sons would have participated in “exercises in writing, spelling drawing, vocal music, gymnastics, declamation [public speaking] and composition.” The Crump sons would have studied using textbooks such as Ray’s Arithmetic 3rd Part, Guyot’s Intermediate Geography (North and South American and the United States) and Hilliard’s Fifth Reader. In the early days of Fisk, the school operated out of former military barracks and buildings.

Thomas Crump became involved in politics during his time attending Fisk. He was appointed to be the delegate from Williamson County to a convention of African American men discussing the interest in large-scale migration of former slaves to Kansas and other states, called the Exoduster movement.

The brothers also would have heard about the creation of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a choir of students who were on a world-tour raising money to construct a new facility for the school which would later be called Jubilee Hall. In two years, they raised over $150,000 and the building was completed in 1876.

|

| Fisk Jubilee Singers ca 1871 By American Missionary Association, publisher - Library of Congress Mary Eliza Walker Crump is on the far right of this grouping |

|

| The_Tennessean_Thu__May_18__1882 |

Thomas and Mary Eliza pursued their singing careers after leaving Fisk. They were active in organizing singing groups to perform for fundraisers in Nashville. In 1882, they organized their "Nashville Ideal Jubilee Singers" to perform at the Tennessee State Capitol. Thomas and Mary Eliza's performances figured prominently in the concert. Later Thomas organized the "Nashville Star Concert Company" to profile local talent and the couple toured throughout the United States performing. By 1889, the couple had moved to Chicago, Illinois where Thomas became a Pullman Porter. While there, Thomas pursued a secondary interest of his - inventions. He filed a patent for an "air ship" that he created. Newspapers throughout the United States reported on his creation.

|

| The_Inter_Ocean June 13, 1889 |

After graduation, Nettie assumed the post of Principal of the “Normal Institute”, a school run by the American Missionary Association in Mound Bayou, Mississippi; she was responsible for about 75 students. During the school year 1900-1901, Nettie returned to Fisk and traveled with famous director John Work II and his newly re-organized Fisk Jubilee Singers. In this photograph, Nettie is the woman standing in the back row on the left.

In October 1879 Granville and Katherine’s second son John married Julia Lytton in Franklin. Their wedding was mentioned in a Nashville newspaper and he was described as a popular young school teacher in Franklin – evidently he was putting his Fisk education to good use.

By the 1885-1886 school year the Crump’s younger children Lafayette and “Antoinette M.” (Nettie) Crump began their studies at Fisk in the Common English Department Class D. The pair worked their way up through the different grades. Both Lafayette and Nettie became school teachers like their brother John. However, Nettie had a more distinguished academic career, even taking classes in Vocal Culture.

|

| Fisk Jubilee Singers 1900-1901 Left to right standing: Noah Ryder, Frederick Work, Nettie Crump, Albert Greenlaw, John Work II. Seated: Ida Napier, Senetta Hayes, Agnes Work, Mabel Grant. |

After her time with the Jubilee Singers, Nettie was appointed the Principal of the Cotton Valley School in Fort Davis, Alabama near the Tuskegee Institute. According to Tulane University, the school “opened with the assistance of Booker T. Washington and the Massachusetts Congregational Women’s Home Missionary Association.”

In 1903 Nettie moved to Augusta, Georgia to assume a new position as a vocal teacher at the Haines School – a private school for African Americans founded by Lucy Craft Laney, a former slave.

Later, Nettie married and she and her husband George Lewis moved to Chicago where Nettie was a vocal teacher. She lived near her older brother Thomas and his wife Mary Eliza who was working as a professional singer. Thomas was working as an agent running a "lecture bureau" called the Metropolitan Lyceum Bureau finding speakers and performers jobs. His wife Mary Eliza was running a successful voice school and performing choir.

Meanwhile, Lafayette Crump - who had attended Fisk with Nettie and also become a school teacher - had returned to Franklin. He married Annie Carter and the couple raised a family in Franklin. Lafayette's youngest daughter Ruth later married Rev. Ephraim Gaylor and the couple operated a boarding house next to Shorter Chapel on Natchez Street. Their elegant home was listed as "Mrs. Gaylor's Guest House" in the famous Green Book in the 1950s.

The Green Book was a listing of places that traveling African Americans could stay while on the road. Due to Jim Crow laws, African Americans often could not stay in hotels or eat in restaurants in the American South, so they needed a guide such as the Green Book to find places to safely stay, eat, and get gas and service for their cars.

Sadly, Granville did not live to see his children’s future successes both vocal and educational. He passed away the same year that Nettie graduated from college. However, both he and Katherine surely would have been proud of all their children. It is an amazing educational legacy that they left - their children reinvested the training they had gained in their communities at a time when teachers and educations for newly freed African Americans were in high demand and very valuable across the South.

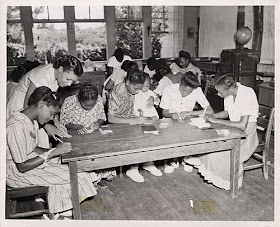

Picture from the Tulane University Digital Library. Cotton Valley School.

|

In 1903 Nettie moved to Augusta, Georgia to assume a new position as a vocal teacher at the Haines School – a private school for African Americans founded by Lucy Craft Laney, a former slave.

|

| Haines School, Augusta, Georgia |

Later, Nettie married and she and her husband George Lewis moved to Chicago where Nettie was a vocal teacher. She lived near her older brother Thomas and his wife Mary Eliza who was working as a professional singer. Thomas was working as an agent running a "lecture bureau" called the Metropolitan Lyceum Bureau finding speakers and performers jobs. His wife Mary Eliza was running a successful voice school and performing choir.

|

| Mary Eliza Walker Crump She ran Walker's Famous Jubilee Singers in Chicago |

Meanwhile, Lafayette Crump - who had attended Fisk with Nettie and also become a school teacher - had returned to Franklin. He married Annie Carter and the couple raised a family in Franklin. Lafayette's youngest daughter Ruth later married Rev. Ephraim Gaylor and the couple operated a boarding house next to Shorter Chapel on Natchez Street. Their elegant home was listed as "Mrs. Gaylor's Guest House" in the famous Green Book in the 1950s.

The Green Book was a listing of places that traveling African Americans could stay while on the road. Due to Jim Crow laws, African Americans often could not stay in hotels or eat in restaurants in the American South, so they needed a guide such as the Green Book to find places to safely stay, eat, and get gas and service for their cars.

| This listing for Mrs. Gaylor's Guest House appeared in the Green Book in 1953; |

Sadly, Granville did not live to see his children’s future successes both vocal and educational. He passed away the same year that Nettie graduated from college. However, both he and Katherine surely would have been proud of all their children. It is an amazing educational legacy that they left - their children reinvested the training they had gained in their communities at a time when teachers and educations for newly freed African Americans were in high demand and very valuable across the South.

|

Excerpt from

Evidences of Progress Among Colored People

By G. F. Richings, 1909

|

On February 24, 2017, at 6 pm, the Fisk Jubilee Singers will be coming to Franklin for a free concert. I hope that everyone will attend and as you listen to the performers, will keep in mind Nettie Crump and her family - and all they had to overcome to achieve so much!